Strange memories on this nervous night near Scranton, in coal-scarred, Appalachian foothills filled with autumn color and political angst

Strange memories on this nervous night near Scranton. Five years since Obergefell. Four since Election Day 2016, when en route to my then-partner’s downtown apartment, the “emergency Sour Patch Kids” and other gas station-miscellany rang to an ominous $6.66.

“Hope it’s not a sign!,” I joked with the clerk behind the Plexiglas. And I carried on, excited to experience my partner’s first American Election Night…in America.

Yet here I am again: In coal-scarred, Appalachian foothills filled with autumn color and political angst. This time, waiting out a pandemic, as well as the returns, with family.

And last week, the United States Senate confirmed Amy Coney Barrett as our newest Supreme Court Justice, thereby cementing the conservative 6-3 majority on the nation’s highest court and potentially jeopardizing marriage equality and abortion legality. No doubt, a fitting end to the first or last four years of an administration that’s waged war on nearly every aspect of sexual and reproductive health rights, from banning trans people from serving our military to forced hysterectomies on our southern border.

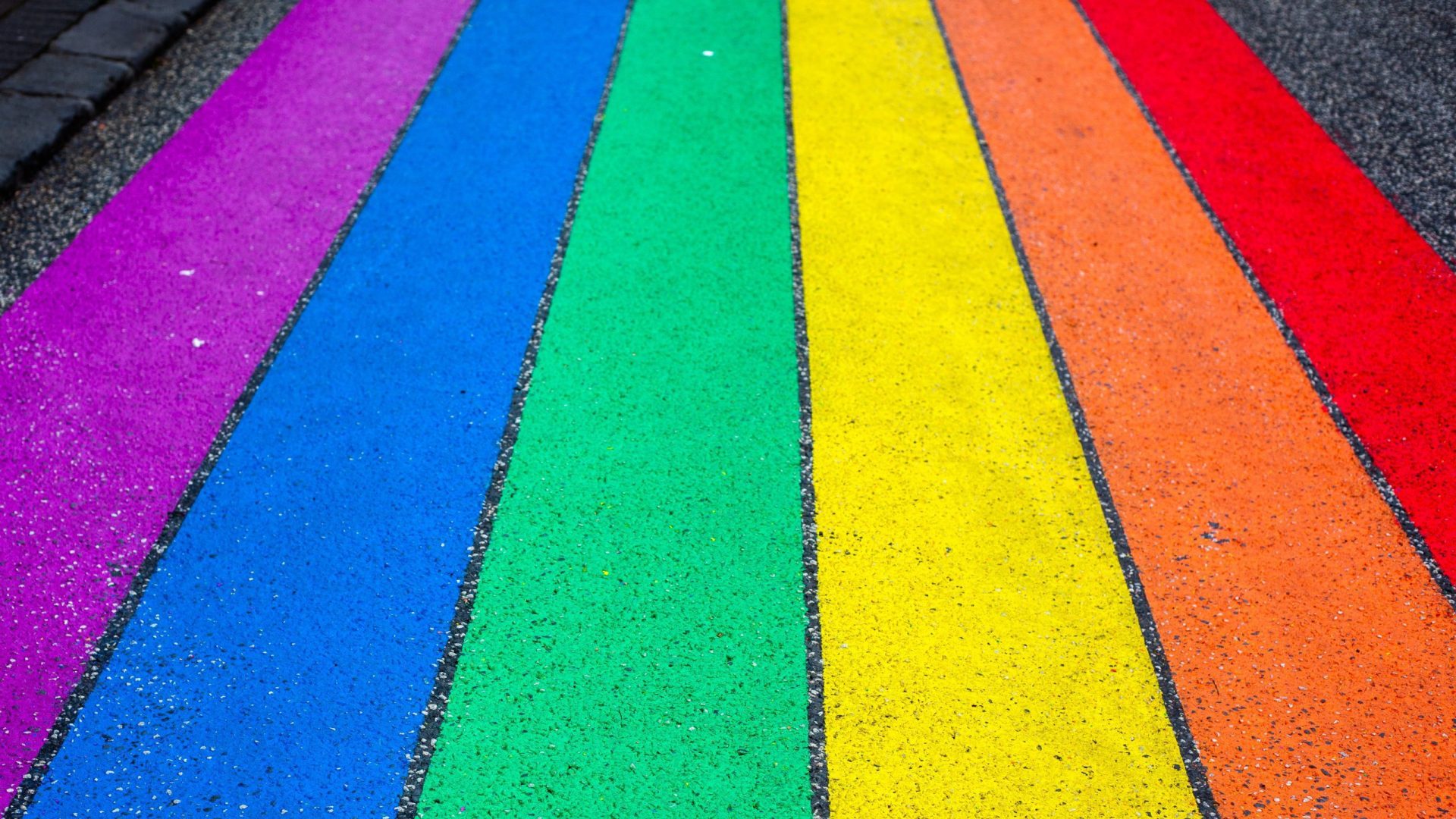

But despite or perhaps because of all this, I can’t help but reflect on the night the Supreme Court announced Obergefell, the decision that legalized marriage equality across the United States—images of a White House illuminated in color, and the hope I felt for my future and for…the future. But, like Hunter S. Thompson1 reflecting on the mid-60s, I can’t help but wonder now if that night seems like the kind of peak that never comes again.

Of course, non-queer readers might be forgiven for thinking “no…”—dismissing this fear with visions of a wave still building—believing history, or at least American history, inherently moves toward a more just and equitable future.

In fact, Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is on my mind a lot tonight—for what emotions better describe our contemporary politics than fear and loathing? And of course, non-queer readers might be forgiven for thinking “no”—dismissing this fear with visions of a wave still building—believing history, or at least American history, inherently moves toward a more just and equitable future. It’s a tempting narrative, an American Dream of love and acceptance, one I, too, once bought into.

It was sometime in 2016.

And in an uncharacteristic move, I just rebuked my uncle for his remarks on the right of people who are transgender to access bathrooms according to gender identity. A designer working in sex education, my heart raced with the need to set the record straight: No, gender is not the same as sexuality. Yes, trans people exist. Yes, they have always existed.

My grandmother sat there quietly, in a housecoat, gray hair in curls. As she listened, a nervous quiver enveloped her chin. The impromptu lecture by me, her grandson, on the biology and sociology of gender was no-doubt too long winded. And when I finished, she offered a story of her own.

In the 1940s, she worked with a transwoman. She fumbled on her words a bit, not knowing quite how to put it, what words or pronouns to use. She and this woman worked in the Empire Silk Mill, an imposing four-story, red-brick structure with a giant smokestack at the bottom of the hill, sewing buttons on garments. In Rustbelt cities like mine, these structures today aren’t lofts or artists’ spaces—they’re just empty. Abandoned.

“Everyone just knew,” she said, as if to gesture to the open door and down the hill and to the town between. In fact, this was a place where everyone knew everyone, everyone with foreign-sounding, Eastern European names like mine, ending in –ko, and –ski, and –nak.

A barrage of these familiar names rolled off her tongue, Polish, Slovak, and Rusyn. “We all worked with her.”

I pressed her. (I needed to!) What was life like for this person in Georgetown? Was she harassed? What happened?!

No—she just was. She just was.

And I sat there, wide-eyed, taking it all in, the latest story in a chronicle of epics connecting me to my past. Out the door and out the window, the town she shared with this woman stretched on, house after house called by familiar names, of families who came to this town across oceans to mine coal in a subterranean both damp and dark in hopes a better life.

Is it simply to see us, the inhabitants of the present, in a kind of rose-colored contrast?

And to me, I think the crux of it all is this: While it’s tempting to think of the past as some ignorant, homophobic, and transphobic era so less accepting than our own, the reality is just more complicated. There is no doubt: This person’s life was likely difficult. But from the perspective of at least one storyteller, this person was accepted…in 1940-something. And you have to wonder: Why is that we color history as a narrative of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil? Is it simply to see us, the inhabitants of the present, in a kind of rose-colored contrast? Is it to absolve us from action on the streets or at the polling place, wishing ourselves through narrative alone as “evolved” and “Good” people?

A queer diaspora.

Yet today, LGBTQ people from this town flee to East Coast cities: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore. Like our ancestors before us, for a better life, for the Dream.

Here, mere miles from Biden’s birthplace, another candidate’s signs pepper the landscape, some unironically reimagining the 70-some-year-old president with bulging biceps and a machine gun in hand. “Make the liberals cry again” or “F*ck your feelings,” they read.

The Trump Administration’s maltreatment of people who are LGBTQ is well-documented. He’s supported employment discrimination against people who are LGBTQ, banned people who are transgender from the military, appointed anti-LGBTQ judges to the courts, opposed the Equality Act, and more. Of those flying these flags, can we be faulted for wondering if this record is for you a feature rather than a bug?

And with that, have we at all progressed in this town since 1940-something? Or has the town once described by the Wilkes-Barre Record as “an immigrants’ rendezvous (1895)” regressed into a nightmare far more hostile for those who don’t speak, love, or act like us?

A decade approaches.

Six bucks and sixty-six cents. It was an omen. While I was excited to see my then-partner’s first election night in America, things didn’t last…in America. In a time of swift-waning queer and immigrant rights, anti-LGBTQ and anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric can really take its toll on a young, queer, mixed-race, mixed-status relationship. Truth be told, we both handled rather delicate situations clumsily, me with my own callow failings and regrets. Strange memories on this nervous night near Scranton indeed.

In a time of swift-waning queer and immigrant rights, anti-LGBTQ and anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric can really take its toll on a young, queer, mixed-race mixed-status relationship.

For the Supreme Court now most immediate—other than any potential vote-counting shenanigans—is Fulton v. City of Philadelphia. This Wednesday, perhaps even before all the ballots are counted, the Court will hear a case to decide whether a taxpayer-funded, religiously-affiliated organization hired by the City of Philadelphia to place children in foster care can, with tax-payer money, discriminate against lesbian and gay couples.

With a newly gained 6-3 conservative majority, the case now serves a stark reminder for all queer people: While support for LGBTQ marriage may be at record highs, our right to the dignity of family now depends on the votes of our friends, neighbors, and fellow Americans—not empty well-wishes.

The only question now is whether they’ll stand with us, as allies, to achieve that Dream, or, whether we’ll one day stand here, abandoned, high in the coal-scarred, Appalachian foothills near Scranton to see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

PHOTO CREDIT: TED GYTAN, FLICKR

1. Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is referenced throughout this work, in italics. For more, see the hyperlink in the opening line.