Sex => Babies. Or is there more to the story?

By Rachel H.S. Ginocchio, MPH

June 6, 2024

For eons, we’ve been explaining human reproduction the same way: babies are the result of sex (more specifically, penis-in-vagina sex). But, with advances in science and medicine, this explanation is no longer adequate. With assisted reproduction, single parents and same-sex couples; those who are trans, intersex, and on the aces spectrum; and those dealing with infertility are also able to reproduce and form families through insemination, in vitro fertilization, donor conception, and surrogacy.

When educators are well-versed in the full gamut of reproductive science, they will be able to comply with the National Sex Ed Standards (SH.5.CC.2): By the end of 5th grade, students should be able to “explain the range of ways pregnancy can occur (e.g., IVF, surrogacy).” In doing so, they will normalize kids’ origin stories and their families. Research shows that students who are heard, seen and respected, do better emotionally, socially, and academically.

In addition, we continue to see ever more examples of assisted reproduction popping up in the media. As more states define personhood as beginning with fertilization (a claim that most scientists don’t agree with) and enact legislation accordingly, the more we need to help our students discuss, debate and understand these very important concepts.

Baby-Making Basics

It takes three ingredients (for lack of a better word) to create a human being: a sperm cell, an egg cell, and a uterus. When an egg and sperm cell joins together through fertilization, they can create an embryo. When an embryo implants in the uterus, it can continue to develop (gestate) into a fetus. If development continues for about nine months, a baby is usually ready to be birthed through the vagina or the abdomen (Cesarean delivery).

Who supplies the baby-making ingredients?

Baby-making ingredients can come from a variety of people.

- Egg cells, sperm cells, and embryos come from an intended parent or a donor. An intended parent is a person who intends to raise a child once they are born. A donor is someone who provides egg cells, sperm cells, or embryos to someone else, so they can create a pregnancy. Egg and sperm cells and embryos can be used right away, or frozen and used at a later time.

- Gestation takes place in the uterus of an intended parent or a surrogate. A surrogate is someone who is pregnant and gives birth to a child for someone else. There are two types of surrogates. A genetic or traditional surrogate is genetically linked to the child, because, in addition to providing the uterus, their egg creates the pregnancy (they are essentially an egg donor and a surrogate). A gestational surrogate or gestational carrier does not share DNA with the child. Though their uterus gestates the child, the egg comes from an intended parent or a donor.

How do the baby-making ingredients work to form a pregnancy?

Penis-in-Vagina Sex (vaginal intercourse).

After sperm are ejaculated into the vagina, they move through the body towards an ovulated egg, in the fallopian tube. If an egg cell and sperm cell successfully join together (called fertilization), they can create the first cell of what can develop into a new human. As the fertilized egg travels through the fallopian tube towards the uterus, it divides to make more cells. When the bundle of cells, called an embryo, reaches the uterus, it can implant (or attach), and can continue to develop into millions of cells over the course of about nine months.

Insemination.

Sperm are ejaculated into a cup or a container (step 1), suctioned out of the container (step 2) and then released into the vagina or the uterus (step 3). Once inside the body, sperm and egg can unite in the fallopian tube—exactly the same way they do during sexual intercourse. Intracervical insemination (ICI) is when semen is placed into the vagina, near the cervix (with a needleless syringe); ICI can be done at home. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) is when sperm are released into the uterus (with a flexible tube called a catheter) and is usually done with the help of a healthcare professional.

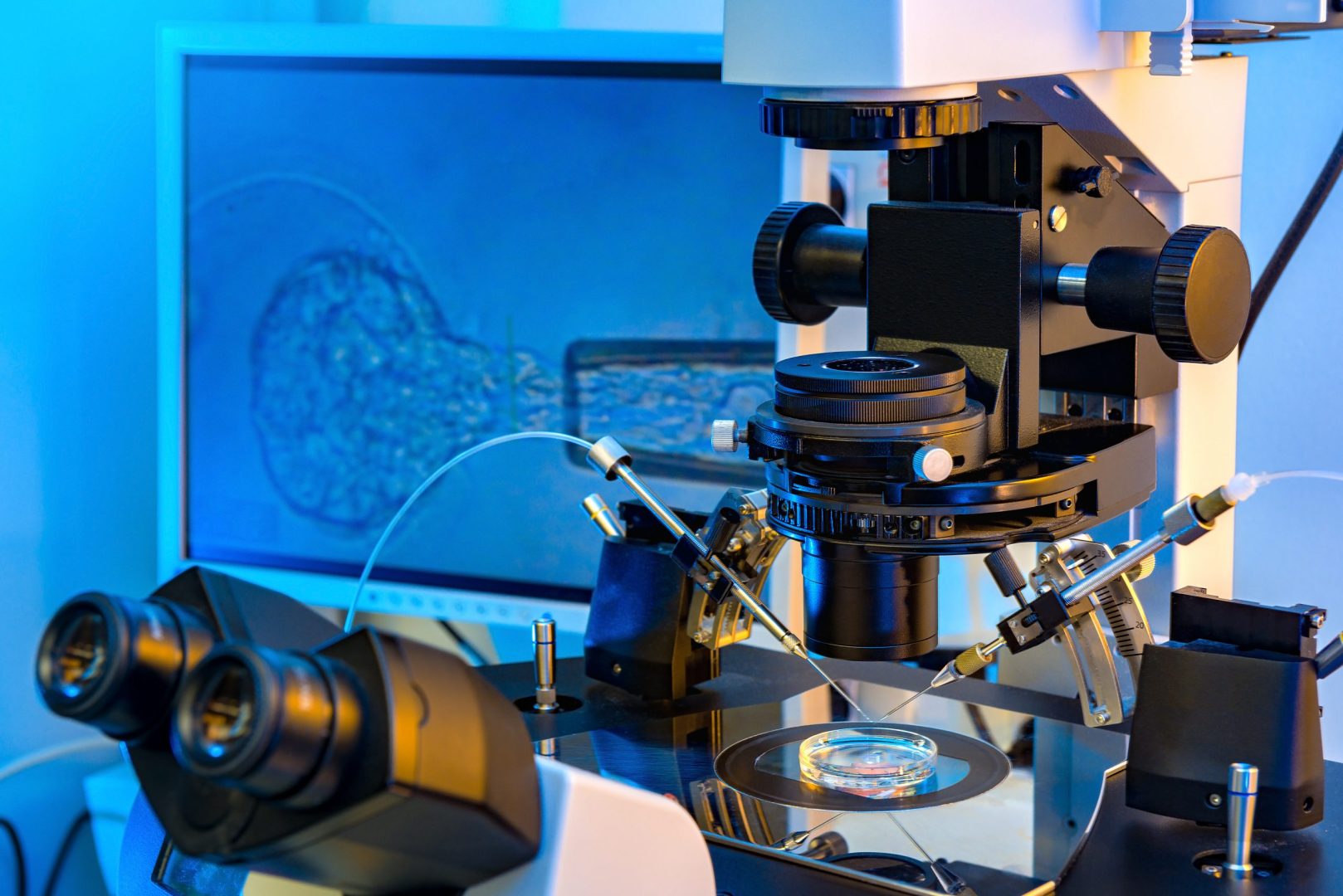

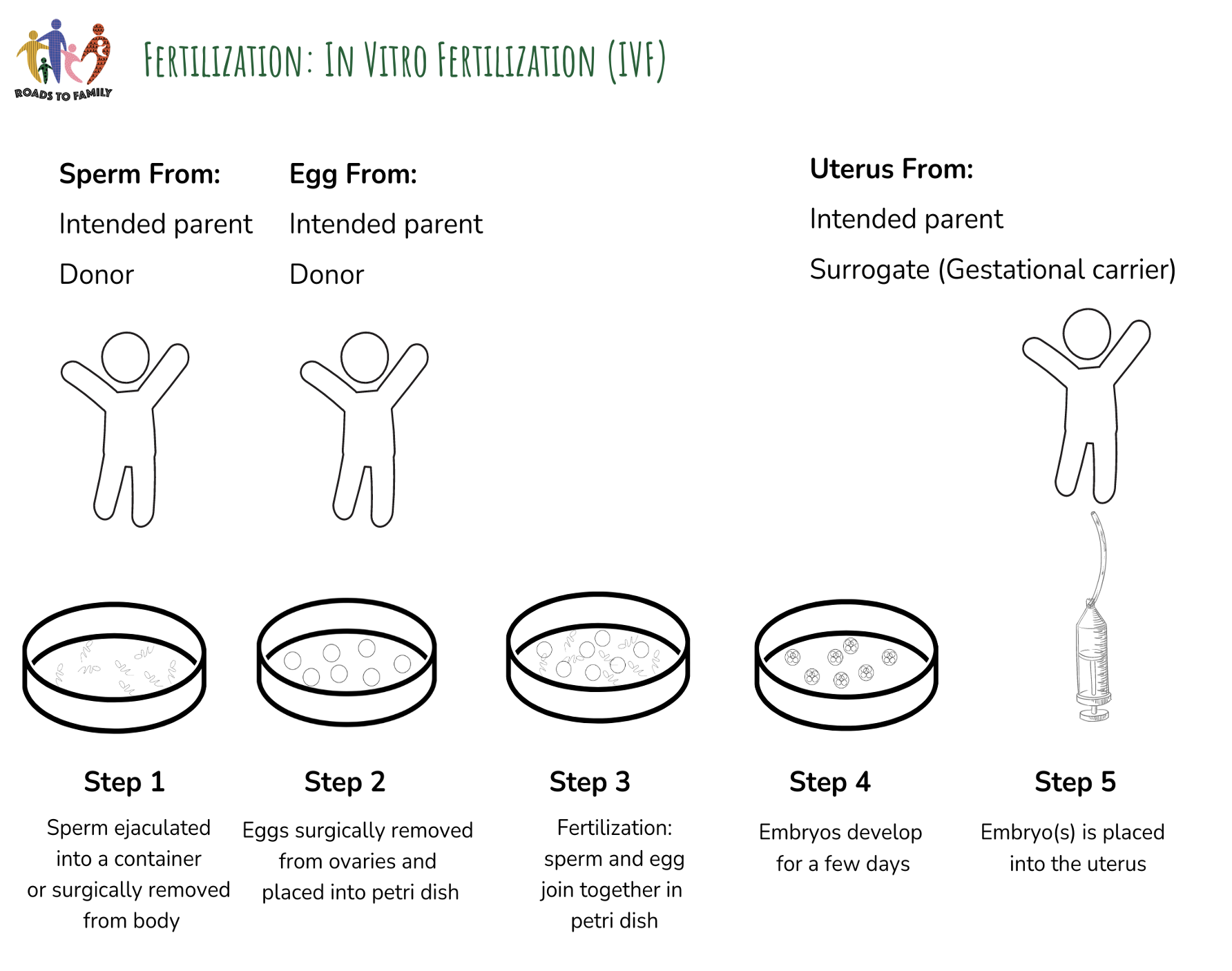

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF).

Sperm are ejaculated or are surgically removed from the body and placed in a container (step 1). Eggs are surgically removed from the ovaries and placed in a petri dish (step 2). An embryologist who is a medical professional specially trained to work with egg and sperm cells when they are outside the body, joins the egg and sperm together (step 3). They either add sperm to the dish with the eggs and sperm “swim” around until they find an egg to fertilize; or the embryologist selects a single sperm and injects it directly into the egg (ICSI). After the fertilized eggs divide in the dish for a few days (step 4), an embryo(s) can be placed into the uterus (step 5) where it can attach and continue to develop—just like it would have if fertilization had happened inside the body. But just like sperm and egg cells, embryos can be frozen and used at a later time or given to someone else.

Infertility is one reason why people use assisted reproduction. Infertility happens when someone’s body is not able to get healthy eggs and sperm from where they are made to where they need to go to create a pregnancy. Additionally, single people, and those who identify as gay, lesbian, transgender, queer, asexual, and intersex (LGBTQAI+), don’t always have all the necessary baby-making ingredients, or choose not to create a pregnancy through sex. There are many instances where donors, surrogates, insemination, and IVF help people form a family.

It is important to remind students that sometimes the people who provide the ingredients to create a child are not the same people who are currently raising the child. This is often true for blended, multi-parent, single-parent, same-sex, extended, cohabitating, adoptive, chosen, and foster families; and for families who use donor conception and surrogacy to grow their family. Families use different names for all the people that play a role in creating and raising children. It’s up to each family to decide who is in their family and what to call them.

Student’s feelings about their origin story and family are often complex and multi-layered, and can change over time. Recognizing, listening to, and respecting student’s experiences helps empower students to manage their feelings and develop a strong sense of identity.

Student’s feelings about their origin story and family are often complex and multi-layered, and can change over time. Recognizing, listening to, and respecting student’s experiences helps empower students to manage their feelings and develop a strong sense of identity.

Why Does this Matter?

Imagine being a second grader, trying to fill out a family tree, and wondering where you should put your aunt, because she is also your parent’s egg donor. Imagine having two dads, and your best friend in middle school insists you have a mom because everyone has a mom, though you have never considered your surrogate to be your mother. Imagine doing blood typing in high school science class and discovering that you can’t possibly be genetically related to your parents. Imagine being in high school sex ed class learning for the millionth time that sex makes a baby when you know your single mom used IVF and an anonymous sperm donor to conceive you, and that your 23andMe results recently revealed that you have twenty-five half siblings. It is these, and myriad other day-to-day experiences that remind us that millions of students all over the world were not conceived via PIV sex.

It is important to tell students that having a more complex understanding of reproduction and families is not about their future fertility (though it will be for many students). It is about better understanding how they came to be in the world, as well as their classmates, friends, and people they read about in the media.

By normalizing all forms of reproduction and family formation, we legitimize everyone’s origin story, and destigmatize all families. Ultimately, youth feel valued and heard; they develop a strong sense of identity and belonging, they treat one another with kindness, empathy and respect; and our schools and communities become a more compassionate place to thrive.

Where Can You Learn More?

Rachel’s book, Roads to Family: All the Ways We Come to Be (Lerner Publishing Group), uses real life stories to explain the science of human reproduction and to explore what it means to shape, find and be family. It’s written for middle and high school students, families, and classrooms and is available through Amazon and wherever books are sold. Rachel encourages you to request that your school and local public library add Roads to Family to their collection, so that students can easily access this resource.

In addition, Rachel, in partnership with Portland Public Schools, GLSEN, Advocates for Youth, and Mariotta Gary-Smith, wrote lessons for 5th and 7th grade and high school about all the ways humans reproduce and form family. You can find these, educator guides, and discussion starters at Rachel’s website: https://roadstofamily.com/ (lessons are also available at the Oregon Open Learning Hub).

Rachel is available for in person or virtual presentations and workshops. Feel free to be in touch with her, through her website.Learn More

Rachel H.S. Ginocchio, MPH holds a Master’s Degree in Public Health (MPH) and has been working in the field of reproductive health and sexuality education for over a dozen years. Through her organization, Roads to Family, Rachel teaches, writes, and speaks about sexual health education, human reproduction and family formation.