A two-part series on why using human-centered design can help us create better resources, programs, and services.

By Milagros Garrido, MS, PMP

July 21, 2021

A s a young woman growing up in the Andes of Peru, nothing irritated me more than seeing many outsiders telling us how to live, do our work, and solve our problems. I could not understand how people who didn’t experience the reality and struggles of living in high altitudes and who didn’t know what it is like to live in a place rich in beliefs, folklore, and cultural practices but also with unreliable electricity and water systems, terrorism, earthquakes, and poverty, could come and try to solve our problems.

The community was never involved in these solutions. Outsiders would come, gather some “data,” translate some research, and create a program, a service, a resource, a solution, and then they would leave and hope for us to maintain “it” and make use of “it.”

Most often than not, the solution will never be used or implemented. And through my adolescent years, I saw youth programs, community clinics, educational pamphlets, and many other solutions and the corresponding labor and capital investment fail and disappear.

Even at this young age, I thought, those solutions failed because outsiders created them without learning from us, asking us if we could even make use of them in the first place. Those creators, researchers, and humanitarian workers suffer a little bit of a savior complex: they thought they knew better, or they didn’t know and didn’t want to learn from us because of where we grew up.

Does this sound familiar? We don’t have to go to an underdeveloped country to see this; we can see it in our projects, in our community, and in our neighborhoods.

Involving the end-user, meaning the beneficiary, the person, or community who will use the solution, should be standard practice. Still, we forget them more often than not.

Involving the end-user, meaning the beneficiary, the person, or community who will use the solution, should be standard practice. Still, we forget them more often than not.

I am not saying that the end-user should have all the answers; no, there is always a place for technical knowledge and stakeholder input. But end-users, especially those who may lack technical expertise, will expose complex pain points and desire simple, elegant ideas that will lead to desirable solutions. And because of this and many other reasons that I cannot fit in this one post, I am a proponent of using and incorporating the Human-Centered Design approach and practices in the sexual and reproductive health field.

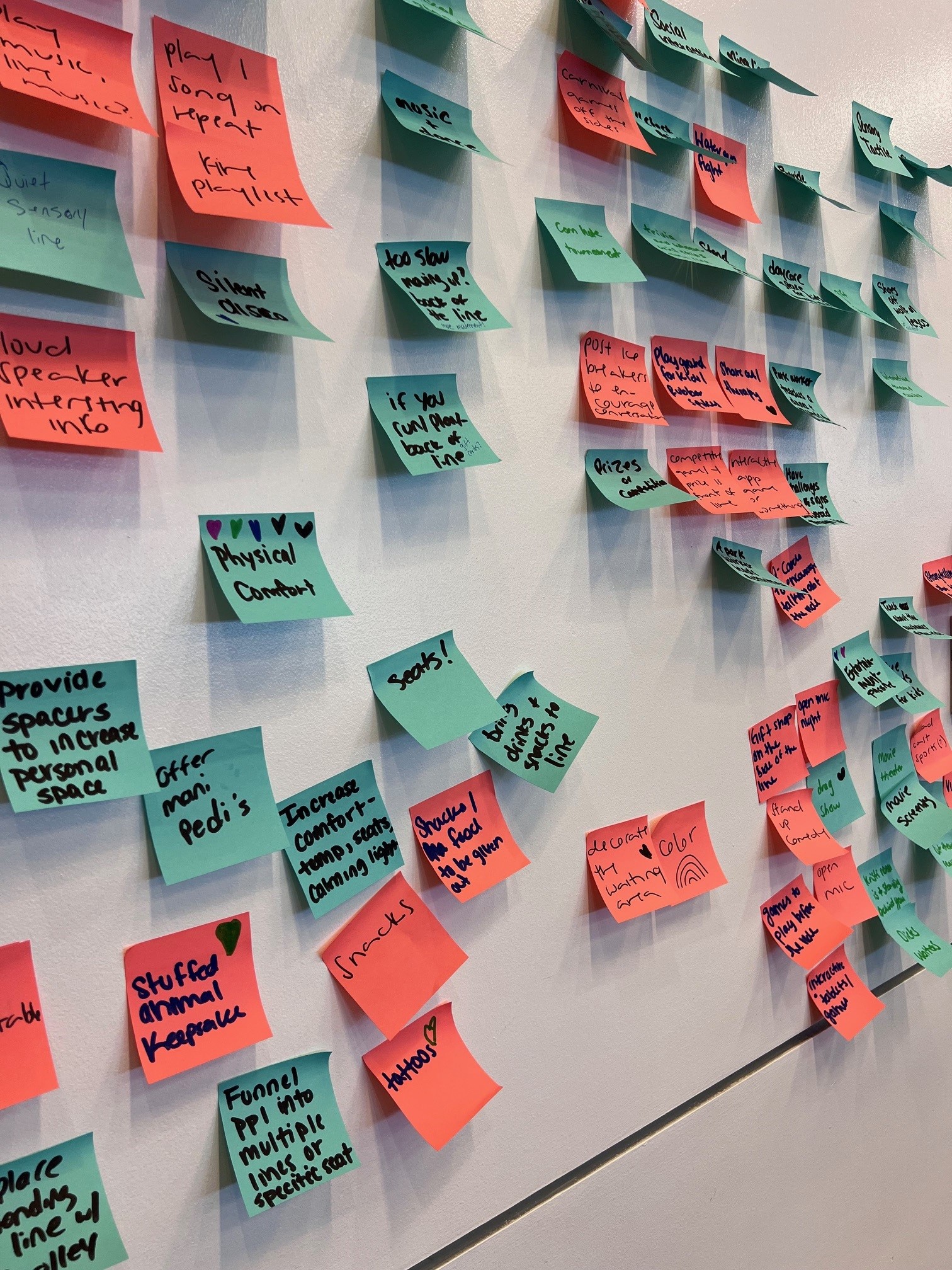

Human-Centered Design (HCD) is a creative problem-solving process that involves the communities we serve in the development of solutions to the issues they face. In HCD, the end–users’ contributions become the backbone of our solutions. HCD also challenges us to see our work differently, especially for those of us who may think of our roles and professions as not as creative.

There are many benefits of using HCD in our work; here there are five (with more to come in my next post!)

- Bring the end-user to the table as co-researchers, co-creator, and active contributors of the solution and see them for more than the problem they face and learn to appreciate and respect them and value their day-to-day experience as expertise.

- Create a solution (i.e., program, resource, products, service) that is genuinely end-user-centered. These solutions will serve their needs better, as opposed to having you impose on them what you think should work and what they should do or not based on your research or technical expertise.

- Tackle your work from a different perspective using other tools and tapping into new talents you didn’t know you have or could gain and cultivate.

- Work and fail quickly (then move on): testing ideas before you spend all of your resources or learn too late that your solution doesn’t work.

- Question your own assumptions and bias and how they impact the solutions that we create for others, in some instances outside our own community, to use.

Still not convinced? Or want to know what this looks like in real life? Wingman Keyboard is one project we’re currently working on, where we used the human-centered approach every step of the way.

Like what you hear? Stay tuned next week for the second part of this blog post series!

Milagros Garrido, MS, PMP, is the Associate Director for our Innovation and Research Department at Healthy Teen Network. Always ready for a challenge, she is at her best when she is finding clever and new ways of using technology to make the seemingly impossible a reality. Read more about Mila.